Understanding the 2020–2021 homicide spike in the U.S.: Causes, variations, and recovery patterns

The United States experienced a sharp rise in homicide rates during 2020–2021, prompting widespread research into one of the most significant crime surges on record. A recently published study by the Manhattan Institute analyzed homicide patterns in 78 large cities, identifying shifts in city-level trends and exploring links to policing disruptions, social unrest, and pandemic-related economic changes. While the study was not designed to evaluate criminal justice reform initiatives, its findings have implications for understanding the social context in which many of these programs were implemented.

Researchers found that the spike in homicides was tended to be more severe in cities and communities already struggling with high baseline violence, with contributing factors including reduced police staffing, disrupted public services, and concentrated group-related gun violence. Surprisingly, unemployment shifts during the pandemic were not consistent predictors of rising homicides, challenging common assumptions.

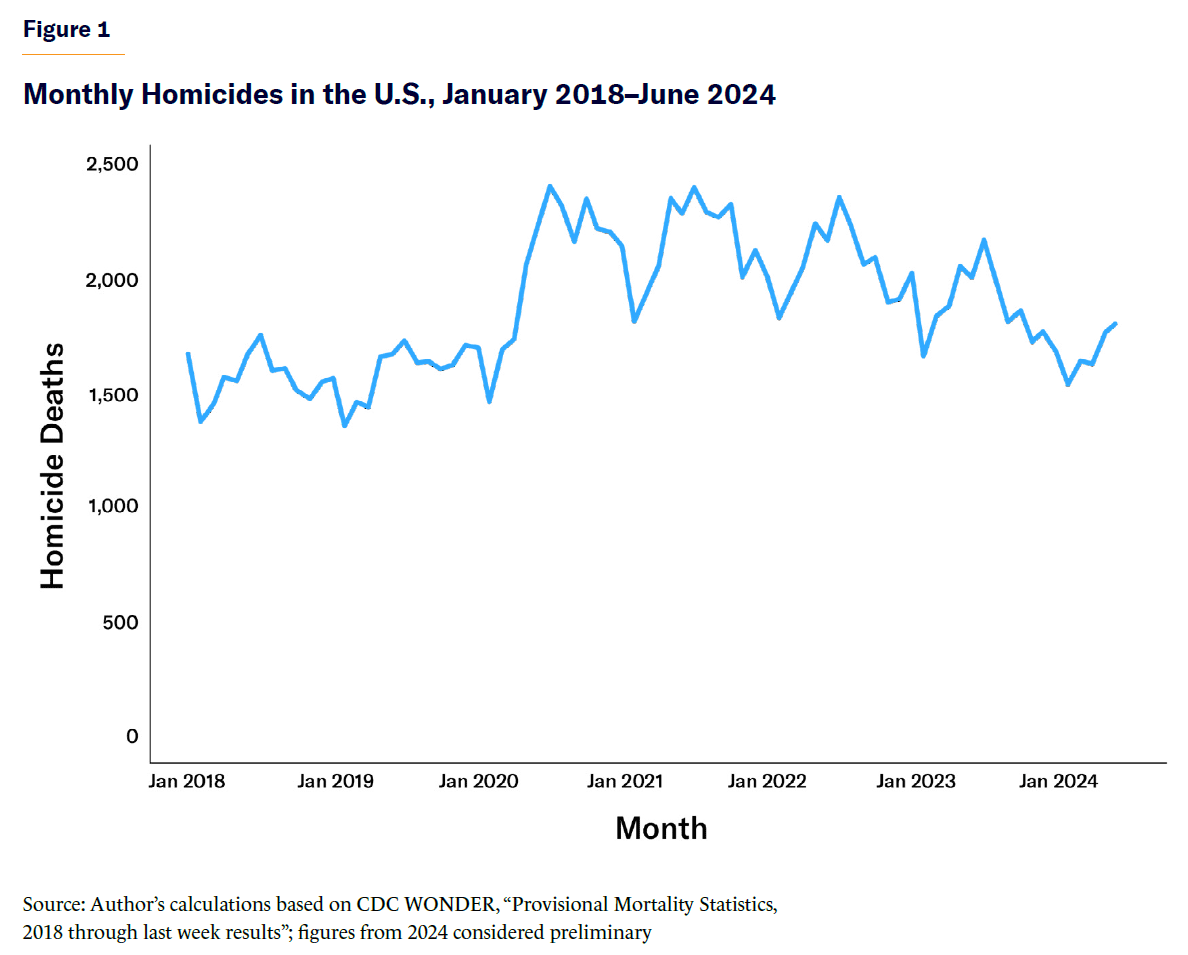

National Homicide Spike

Homicide rates in the United States rose by 30% in 2020, marking the largest single-year increase in homicides in over a century. Elevated homicide rates persisted through 2021 but began normalizing over the next two years, resembling those of 2018 and 2019 by mid-2024. As established by the research, the initial rise in homicide rates corresponded with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which was exacerbated by social unrest following the death of George Floyd. The Manhatten Institute study categorized the period into three phases: 1) Baseline (2018–2019), 2) Spike (2020–2021), and 3) Recovery (2022–2023).

Source: Manhattan Institute (2025), Spike and Recovery Homicide in Big Cities, 2018–23.

City-Level Analysis

Analysis of cities’ recovery from homicide spikes reveals diverse outcomes. Researchers found that cities with higher initial homicide rates prior to the spike period experienced the largest absolute increases in homicide rates. However, looking at proportional changes, which allow for a focus on how much a rate has increased relative to its original figure, painted a different picture. For example, St. Louis and New Orleans had very high baseline homicide rates and also saw some of the largest raw increases. However, because their starting points were already elevated, these increases appear less dramatic when looking at proportional increases. Yet, from a public health and safety perspective, any increase in these high-crime areas is often much more damaging because these cities already face considerable social and economic challenges. Even a modest uptick in their homicide rates can be indicative of serious destabilizing trends.

In contrast, Portland, Mesa, and Austin had relatively low homicide rates before the pandemic, and experienced the largest proportional increases. In these cities, a jump from 5 to 10 homicides per 100,000 people is still a 100% increase, which feels much more significant relative to the city’s previous experience with crime. For example, Portland, which started with a homicide rate of about 4.2 per 100,000, saw its rate more than double to 10.5 per 100,000 in the Spike period, representing a massive disruption in the social fabric and the capacity of the local justice system to cope with crime. States with significant social unrest following events such as the death of George Floyd, like those in the Midwest and Northwest (e.g., Minneapolis, Portland), experienced higher proportional increases. The unrest likely disrupted social order and also led to reductions in proactive policing. In the case of Portland, for instance, much of the increase in violence was attributed to the police defunding movement, which significantly reduced police staffing and resource allocation.

Some cities experienced impressive recoveries, reverting close to pre-spike homicide levels. For example, St. Louis nearly fully recovered, but to an extremely high baseline, with the highest homicide rate in the sample across all three periods. Meanwhile, cities Miami, Buffalo, and Nashville experienced spikes of at least 20% but then recovered to within 10% of their starting value. Other cities did not recover so well, with homicide rates that remained high or even continued increasing in the Recovery period. This is particularly concerning among cities that already had high baseline rates. For instance, Cleveland, Milwaukee, Memphis, and New Orleans had baseline homicide rates above 15 homicides per 100,000 population, experienced spikes of at least 40%, and recovered by less than one-third.

This correlation suggests that high baseline rates may predict poorer recovery outcomes. However, this was not universally true, as there were a few strange anomalies. For example, Portland started from a low baseline, saw the largest homicide spike in proportional terms, and continued to see increases even as the nation as a whole recovered. In contrast, Baltimore’s homicide rate has consistently been one of the highest among U.S. cities, with the second-highest baseline homicide rate (54 per 100,000, behind only St Louis). Yet, the city did not see a sharp proportional uptick in homicide rates. This contrasts with cities like St. Louis or New Orleans, which experienced significant spikes. Further, some cities were resilient against the homicide spike altogether, such as Anchorage, Honolulu, and Newark, New Jersey. For the former two, it’s quite possible that being outside of the contiguous United States played a role that made these two cities different than the others. The same cannot be said for Newark, however.

Ultimately, these diverse outcomes underscore the complex, interwoven factors ranging that shaped each city’s response to the crisis, emphasizing that no single factor can fully explain the fluctuations in homicide rates.

Unemployment and Crime

The study found that while unemployment was modestly correlated with homicide in the baseline period (2018-2019), where a clear pattern emerged showing a correlation between unemployment rates and homicide rates across various regions. This correlation supports a well-documented theory in criminology that socioeconomic factors, such as job availability and economic stability, can influence crime levels.

However, when the analysis shifted to consider changes in unemployment rates (comparing the baseline period to the spike period), the impact on violence and homicides was statistically insignificant. This suggests that while unemployment may generally be associated with violence, it does not necessarily predict specific changes during these tumultuous years. Cities that experienced some of the sharpest rises in homicide, such as Louisville, St. Louis, and New Orleans, did not see corresponding changes in unemployment. Conversely, some cities with high unemployment did not suffer a major rise in homicides. In essence, even as unemployment may have risen dramatically during the pandemic, it did not lead to a predictable increase in violent crime.

This disconnect challenges longstanding assumptions about economic distress as a driver of violent crime and suggests other crisis-related factors may have played a more pivotal role. This perspective advocates for deeper investigations into the multifaceted causes of crime, especially during unprecedented times. Factors such as changes in policing practices, law enforcement responsiveness, community engagement, social services availability, and even broader societal conditions (e.g., mental health crises, social isolation) may overshadow the impact of mere economic factors like unemployment.

Law Enforcement Dynamics

One of the study’s main findings relates to reductions in proactive policing during the pandemic and in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder in 2020. Proactive policing refers to officers actively engaging in measures to prevent crime before it occurs, rather than solely responding to incidents after they have happened. This can include strategies such as community policing, increased patrols in high-crime areas, and proactive investigations aimed at deterring criminal activity. The 2020 homicide surge coincided with a dramatic drop in proactive policing across many jurisdictions. This was partly due to pandemic-related staff shortages, but also to widespread anti-police protests and rising criticism of law enforcement, particularly in major cities. Cities with both high homicide rates and significant pullbacks in policing (e.g., St. Louis, Milwaukee, and Atlanta) were especially affected.

This decrease in proactive policing may correlate with the rise in certain types of violence, especially gun-related and gang violence. However, because law enforcement practices vary quite a bit across localities, the relationship between police activity and homicide rates is likely nuanced. While strong local law enforcement practices may act as a deterrent to crime, gaps in these practices could exacerbate violence, particularly during high-stress periods. According to the Manhattan Institute study, when police departments experienced increased turnover, resignations, or a shift in focus towards managing protests and community dissatisfaction, the effectiveness of proactive policing diminished. This could have created an environment more conducive to crime, with potential offenders perceiving reduced risks of apprehension.

Another important consideration is police staffing levels, which is crucial for the effectiveness of law enforcement agencies in managing crime. The study identifies a noticeable relationship between changes in police staffing and shifts in homicide rates during the Baseline and Spike periods. Cities that started with higher homicide rates and saw significant reductions in police personnel typically experienced more substantial increases in homicide rates. The findings highlight the need for law enforcement agencies to focus on maintaining adequate staffing and implementing proactive measures that foster community engagement and trust, aiming to reduce overall crime rates and improve public safety effectively.

Outliers and Anomalies: Portland and Baltimore

Not all cities followed these trends. Baltimore, for example, had one of the highest baseline homicide rates but did not see a dramatic increase during the spike. Portland, on the other hand, had a low baseline but experienced a record-breaking homicide surge. These anomalies support the idea that local dynamics play an important role in the homicide increase and merit further study.

Portland

According to a homicide analysis from the Portland police department, from 2019 to 2021, homicides became increasingly concentrated among a small segment of the population, with only about 0.1% directly involved. Gun homicides rose significantly, making up 75% of all homicides during this period, compared to 60% from 2015 to 2019. Over half of these were linked to gang-involved individuals, with around 30 active gangs and 1,000–1,495 members citywide. Nearly one in five gang-affiliated individuals were involved in a homicide or shooting during the study period, pointing to a high-risk, tightly connected group driving much of the violence. Group violence tended to stem from ongoing disputes and retaliations, with retaliatory shootings occurring, on average, 125 days after an initial violent incident. Public safety efforts are urged to focus on these high-risk networks to interrupt cycles of violence.

According to a data published in 2025, gun violence was also highly concentrated among a small group of individuals and geographical areas: 77% of firearm homicides occurred in 26 disadvantaged neighborhoods, and houseless individuals—who made up 38% of all homicide victims—were found to be 650 times more likely to be killed by gun violence than housed residents. The top drivers of gun violence included gangs/groups (33%), domestic violence (12%), housing instability (12%), robbery or stolen vehicles (8%), and personal disputes (8%).

Baltimore

Baltimore’s relative stability in homicide rates during 2020–2021, despite historically high crime levels, makes it a compelling anomaly. Some researchers postulate that the city’s policing strategies contributed to its unusual trajectory.As highlighted by a 2022 study, Baltimore underwent significant police reform in the wake of the 2015 Freddie Gray incident, fostering better relations between law enforcement and communities. This focus on community trust and engagement likely allowed the city to maintain a degree of operational capacity during the pandemic and unrest, in contrast to cities like Portland, where reductions in police presence exacerbated crime rates. The police department may have been able to continue effective crime prevention efforts, despite reduced resources, allowing the city to avoid the extreme spikes in violence that other places experienced.

The city’s socioeconomic context also may have played a critical role in shaping its response to violence. According to a 2025 study, Baltimore’s long-standing issues with inequality and poverty may have contributed to a sense of normalization around high crime rates. Communities accustomed to high levels of violence may have developed coping mechanisms that helped absorb the shocks brought on by the pandemic and civil unrest. While many cities saw crime spikes as a result of economic and social disruptions, Baltimore’s history of violence may have created a resilient infrastructure that was better equipped to manage these challenges.

In sum, Baltimore’s experience suggests that a mix of policing reform and adaptive social infrastructure can help cities weather periods of acute instability. Its trajectory offers valuable lessons for designing durable public safety strategies, particularly in urban areas with histories of concentrated violence. Understanding these nuances can critically inform future public policy and community safety initiatives aiming to manage and mitigate interpersonal violence, particularly in urban settings.

Conclusion

These findings reveal a complex web of potentially related factors offers critical insights into how future crises may affect public safety. First, the sharp increase in homicides during 2020–2021 highlights the profound impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and social unrest on public safety. The findings from the Manhattan Institute’s study suggest that factors such as pre-existing violence, police presence, social unrest, and community resilience played pivotal roles in shaping homicide trends. Cities with already high crime rates faced the largest increases, but recovery varied widely.

The study also challenges the conventional wisdom that unemployment is a primary driver of crime, instead pointing to the importance of factors like policing practices and community dynamics. Moving forward, the complex web of influences on crime rates must be carefully considered in crafting future public safety policies. By focusing on proactive policing and community engagement, cities may be better equipped to navigate future crises and mitigate the impacts of violence.